Some Incomplete Thoughts on Critics, Haters, and Artistic Validation

I feel compelled to poke my head out of the Treehouse of Overwork long enough to offer some brief, vague, and half-formed thoughts about the interesting discussion occurring right now in webcomic-land about Internet trolls and their effect on creative people. Zen Pencils makes the case for Art Triumphant with a visually and viscerally compelling four-part serial (see parts 1, 2, 3, and 4). Chainsawsuit makes a cerebral counterpoint here. Read both, enjoy, and let them get you thinking.

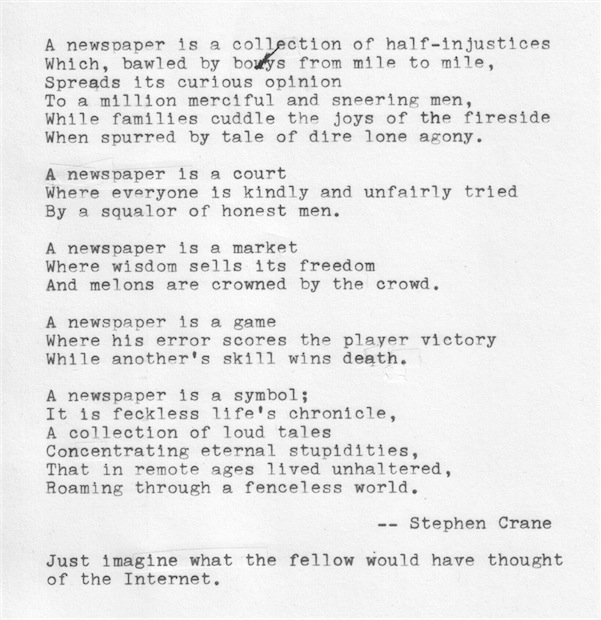

And now for my $0.02: Creative writers go through the same thing. I’ve had this discussion, or variations of it, with poets, novelists, etc. over the years. And the one thing that rings clear to me is that the response to critics and/or haters has more to do with how closely writers identify with their work. The more personal someone’s work is to them, the more criticism stings and the more haters get to them.

I tend to land on the chainsawsuit side of the issue, mostly because of the way I identify — or don’t identify — with my work. People think I’m being pedantic when I say “I write” rather than “I’m a writer,” but to me the distinction is really important.* Writing is something that I do, it’s not what I am. And as a result, when people criticize my work on the merits, a little piece of me doesn’t die every time. If there’s something that I can learn from the criticism to improve my work, I try to learn from it. That being said, it’s up to me as the writer to take the criticism on its merits and take away anything of value that might help me do better next time. (That’s not to imply that every critic has a nugget of wisdom to share; there are a lot of obtuse people out there.)

With insecurity often comes defensiveness. We react to harsh criticism by claiming a superior high ground. We console ourselves and others by saying that it’s easier to just sit there and throw darts at someone than it is to go out and actually create something that never existed before. Objectively, that’s true, but here’s the thing: creating something that never existed before doesn’t automatically mean you’re a better person. It just makes you a person who creates things that never existed before. You are not a superior person because you do that. Creating things that never existed before is your job.

If someone tells you that you did a bad job, either they’re right or they’re wrong. If they’re right, learn from the critic and do better next time. If they’re wrong, ignore them. That’s it.

That’s not to say that the creative act should be devoid of emotion and personality. You pour a lot of heart and passion into your work. Of course you do: you care about it. But then, when it’s done and out there, it’s standing on its own. It’s not attached to you with an umbilical cord, it’s not an appendage of your body. If you treat it that way, then the praise and criticism of the work become praise and criticism of you the person. Instead of always feeling satisfied that you worked hard and applied your skill to create something that didn’t exist before, you end up feeling good or bad depending on whether people like or dislike the results. You have given the critics the power to validate you the person, not simply to offer their opinions of your hard work.

Rather than risk blundering headlong into the whole “art vs. craft” debate that people who write are always having, I’m going to stop now. Like I said, this is all half-formed stuff that’s probably not ready for prime-time. I just felt the urge to throw this at the wall and see if any of it sticks, so I can come back to it later and see where it takes me.

—

* = Or the time that I was chatting with a young writer who said, “It must be nice to get paid to be a writer,” and I replied, “I’m not paid to be a writer. I’m paid to write,” and he got pissed off and stopped talking to me. I wasn’t trying to be a smart-ass; I really think there’s an important distinction there that a lot of inexperienced writers don’t get. If you think you’re going to find an editor who is willing to subsidize your writerly lifestyle, you’re absolutely in the wrong line of work.

Tomorrow I’ll be staffing the

Tomorrow I’ll be staffing the