Caught in the Web (a Really, Really Long Post)

The Verizon/NSA/FISA issue has alarmed a lot of people to varying degrees, and for many different reasons. Now, my rational side agrees with writer David Simon, who expressed his thoughts on the matter here and here. TL;DR:

“. . . the Verizon call data should be used as a viable data base for counter-terror investigations and […] its misuse should be greeted with the hyperbole that currently adorns the present moment. On the other hand, […] while I still believe the differences between call data and a wiretap are profound, and that the standard for obtaining call data has been and should remain far more modest for law enforcement, the same basic privacy protections don’t yet exist for internet communication. There, the very nature of the communication means that once it is harvested, the content itself is obtained. And the law has few of the protections accorded telephonic communication, and so privacy and civil liberties are, at this moment in time, more vulnerable to legal governmental overreach. That’s a legislative matter, but it needs to be addressed.”

But while Simon’s argument seems relatively clear-cut and logical when taken in the abstract, it becomes something else entirely when zoomed down to the scale of the intimately personal.

See, I know what it feels like to find out that someone has been listening to your phone calls. Because recently, I learned that someone had been listening to mine.

1. The Letter

One day late last year, I received a note from the mailman that a certified letter was waiting for me at the post office. I couldn’t guess what it might be for, but I figured it might be related to taxes or insurance or some routine thing. So I drove down to the post office, stood in line, and waited to pick it up. After I handed my ticket to the clerk and she returned with it, I glanced at the return address and felt a gut-punch of unease.

U.S. Department of Justice

U.S. Attorney’s Office

District of Connecticut

What the hell? Connecticut? Huh? That’s my home state, and I have relatives there. Oh, man, did a cousin do something stupid or something?

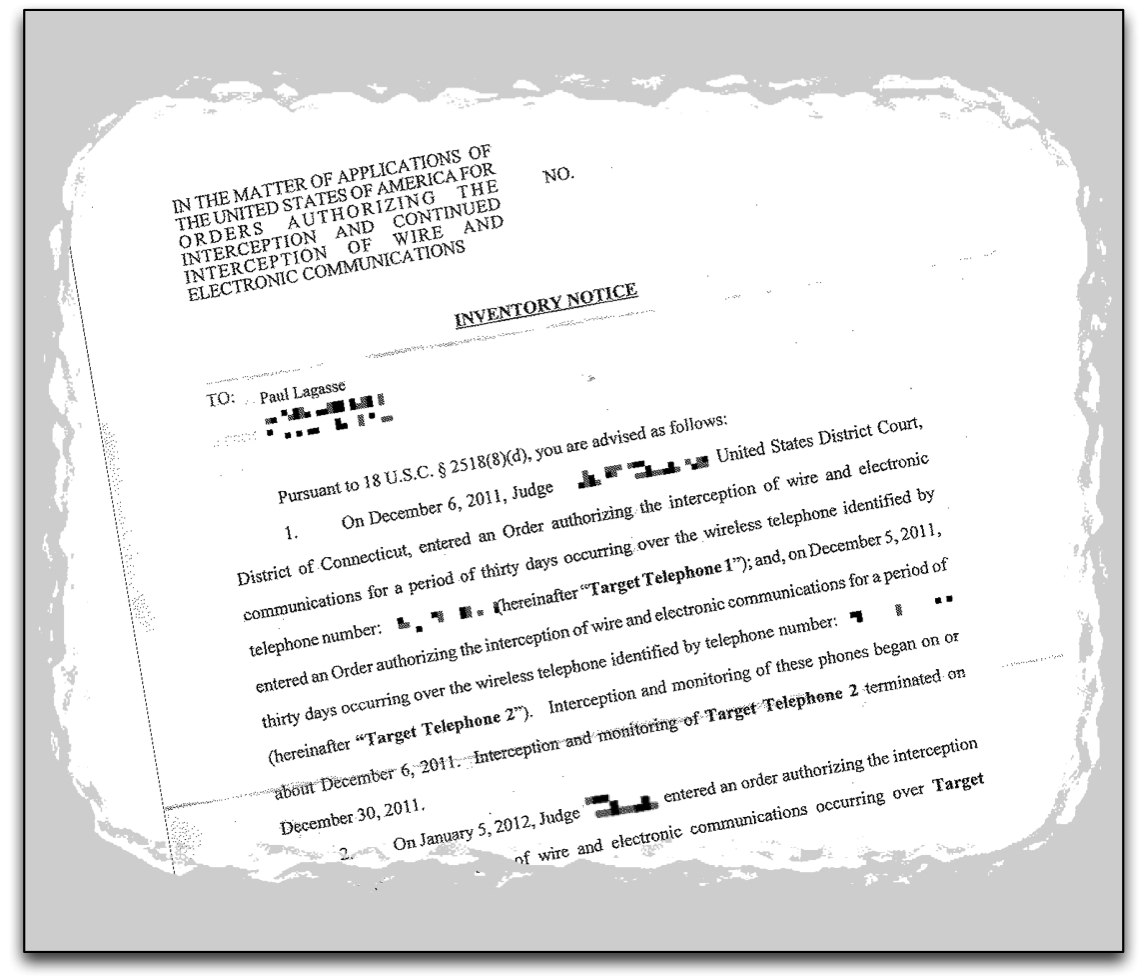

Unable to wait until I drove home before opening the letter, I found an empty patch of countertop by the window and opened the letter. I’d be lying if I said my hands weren’t trembling just a little bit. As I quickly scanned the very official-looking letter, the keywords popped out at me, each one causing a stone of confusion and uncertainty to fall into my stomach. In the matter of . . . interception of wire and electronic communications . . . pursuant to . . . you are advised as follows . . .

There followed a three-page list of dates, phone numbers, and in big bold letters “Target Telephone” followed by a number. Target Telephone 5. Target Telephone 6. Altogether, nine Target Telephones. None of them I recognized offhand, and none of them, I was relieved to see, were mine. I noticed, with a growing sense of surreality, that each paragraph was numbered. As if this was just someone’s to-do list.

Only when I reached the final paragraph, Paragraph 10, on the last page of the letter, did this Matrix-like cascade of numbers and words suddenly coalesce with a crystal clarity that made my heart pump so hard that I actually felt the arteries in my neck swell: “You are receiving this notice because you were intercepted during one or more of the authorized periods of interception. If you have any questions regarding this notice, please contact Special Agent . . . ”

If I had any questions? If I had any QUESTIONS??? You’ve just told me that I’ve been talking with someone or someones unknown to me who was being wiretapped — wiretapped! — by the FBI, and you think I might have questions?

As soon as I got home — a shaky ride — I put in a call to the Special Agent and got his voicemail. I left him a message explaining I had just received the letter and, yes, I had some questions, and to please call me back.

A day went by. No response. I called and left another message. No response. I called his field office and tried to speak to someone else who could help me. No one could. Meanwhile, the drumbeat of questions were just pounding louder and louder in my head, along with the uncertainty.

Was I in trouble? Was I a potential witness in some pending trial? I knew I had done nothing (knowingly) illegal, but did that matter? Was there any kind of guilt by association from having talked to — who, exactly? Did I have to worry about, I don’t know, threats from the person who got bugged? Did they get arrested? Have I been talking with a terrorist?

Trust me, the questions come as thick and fast as the flywheel of the imagination can build its momentum. At some point you just have to rein it in, put the brakes on. But you begin to understand just a little bit about how some people can become paranoid.

I dug up all my notes from the five months (five months??) that the wiretaps had been authorized. I cross-checked all the numbers against anyone I had interviewed for articles I had written during that time. I checked the numbers against family members in my address book. And all the while I waited to hear back from the FBI Special Agent, who never did call back by the way.

I contacted an expert in national security whose e-newsletter I have subscribed to since library school (ironically, government transparency and classification are issues of personal interest to me — surely a coincidence, right?). While he shared my concern, he could only offer some general (but very welcome) advice, and suggested that I speak with a lawyer who specialized in surveillance law.

Okay, look. Like most ordinary, dull, boring, average citizens, I don’t interact with law enforcement on a daily basis. So the first time in your life you hear the words, “maybe you should speak to a lawyer,” you suddenly realize that you’ve probably crossed some kind of boundary. Last week, I’m a self-employed writer minding my own business. And suddenly now I’m faced with the prospect of becoming one of those people you hear about.

The attorney I spoke with was a very collegial fellow, but as I explained my situation and then said the words “Inventory Letter,” he grew suddenly serious.

“Have you done anything that you should be worried about?”

“What? No!”

“Then you don’t have anything to worry about.”

And I reluctantly admitted that that’s really the only option I had left. I hadn’t done anything wrong, so I shouldn’t worry about it. About any of it.

2. The Reductio ad Absurdum

Now, all during this time I had been deep-diving the web in search of anything that could shed some light on the letter and the proceedings. Late into many sleepless nights, I read a lot of FBI manuals and legal opinions and court cases and and federal policy and polemics and screeds and paranoid rants from the tin-foil-hat squad. I gave myself a crash-course in the history and law of surveillance and wiretapping in the United States. All just so I could find out what this letter meant.

Turns out that inventory notices like the one I received can be issued by judges after an investigation is completed to inform people that they had been surveilled. Essentially, telling them,

We just wanted you to know that, at some point over an extended period, we listened to one or more of your conversations with one or more persons who we can’t name. Sincerely, the Justice Department.

I also learned, incidentally, that judges don’t have to require the FBI to issue inventory notices. So I guess I should feel grateful to the judge for insisting that I be told. How many other people got this same letter? How many people wondered, like I did, what it really meant, and what the implications were for them?

Is this the logic that we have been reduced to: “Hey, that letter is proof that we’re not living in a totalitarian surveillance state — because in America, we may (or may not) actually tell you when we’ve been listening in on your conversations”?

3. The Bottom Line:

Look, I’m not trying to blow this out of proportion. This was just one ordinary person’s very tangential brush with a completely legal and fairly routine event involving federal law enforcement officers doing their job.

But even that glancing, momentary encounter changed something fundamental in my life. One day I received a letter and found inside a couple of pieces to a puzzle and a note saying that I’m not allowed to know anything else about the puzzle.

From that letter I learned that, in the invisible world, someone unknown to me had decided, for reasons equally unknown, that I needed to know that people whose names I will never learn once listened to me talking with someone else on the phone. They decided that I had a right to know that they had legally invited themselves into my conversation, and had remained there, silent, listening to me.

So while I agree intellectually with David Simon and others that these things are legal and that, taken in the aggregate, they are probably saving lives as we speak, I also know that ubiquitous surveillance also has another, profound, effect as well.

As more and more ordinary people like me have a glancing encounter with some part of the ever-growing national security apparatus, more and more of us will probably find ourselves unwittingly looking over our shoulder. Catching ourselves before speaking our mind. Second-guessing people’s motives. Seeing ghosts. Wondering if a friend is keeping secrets from us. Wondering if someone is listening to us.

Is that gradual corrosive effect too high a price to pay for our collective safety? I don’t pretend to have an authoritative answer to that. But personally, right now it feels that way.

Categorised as: Life the Universe and Everything

Comments are disabled on this post

Fascinating. I had no idea that such notifications were issued (and in the antique fashion of a piece of paper that you must travel to collect, no less).

You make a lot of good points here. The lawyer’s comment reminds me of Eric Schmidt (Google CEO’s) disingenuous comment, “If you have something you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it.” We are supposed to be internalizing the awareness that Big Brother may be watching at any moment (and Big Corporation, and Little Hacker, and Little Terrorist). Modern communications are a battleground for the forces of security and insecurity. I’m glad I have my typewriters and the option of sending a message the antique way, on a piece of paper.

Yes, it does seem bizarrely quaint to have been notified by certified mail! The lawyer’s comment might as well have been spray-painted on the brick wall at the end of the last turn of the labyrinth.

I haven’t entirely given up yet (I still keep the letter folded on my desk), and this new stuff has certainly stirred up the emotions again. Maybe when I have more time, I’ll pick it up again.

Next step is for us to set up a courier network for our typewritten missives! 🙂

Re: the courier network — something like that played a role in my 2010 NaNoWriMo novel.

Intersting post. I have mixed feelings of the lastest ‘spying’. It seems Orwell (1984) and Steppenwolf (Monster) were right. We are being watched. Not just with this latest, but even with satellites.

Privacy is being lost, but then how do we as a civilized society defeat the terrorists and others who would like to destroy us if we cannot monitor communication channels of any sort?

Like I said, I don’t pretend to have the knowledge or the expertise to begin to answer those big questions with any authority.

Surveillance is nothing new. What is new, it seems to me, is the sheer ubiquity of it — and, along with that, the ease with which we have allowed it to pervade every nook and cranny of our society. And now, people are beginning to realize the implications of their acquiescence.

When it comes to this issue, I am reminded of Neil Postman’s view of technology. A technology in and of itself is neither good nor bad, but it does create consequences, and most of those are probably going to be of the unforeseen variety.

So with that analogy in mind, my concern here is pretty narrowly limited. I’m not as concerned with the intentions behind the government’s surveillance policies and procedures, or those of the law enforcement officials charged with carrying them out, but rather with the consequences for the people they are designed to protect.

Whether or not increased surveillance is the right way or the best way or the ethical way to stop the bad guys, or the lesser of two evils, or whatever, I believe it is going to have some pretty big consequences for how we define our way of life, our roles as citizens, and what we define as the commons. And I don’t think we’ve been looking at that seriously.

I keep seeing this kind of data collection cast as necessary to win the war on terror, but clearly, once it’s begun, it’s not going to stop.

In other words, some might trust their government right now, but what happens ten years from now when the “war” is over, and the spying isn’t?

Also, I have to wonder. If you aggregate every aspect of data collection on ordinary citizens into one giant pile of data, wouldn’t it violate the Fourth Amendment?

Clearly, the court thinks collecting phone metadata doesn’t violate the 4th, but when you lump in online tracking, email, smartphone tracking and a few other goodies, I’d suggest we’ve got something of a Fourth Amendment singularity.

I agree, we’re barreling headlong into some constitutional thickets.

And I have no doubt that, at some point when the “war” has been declared “won,” the spying apparatus is going to start plying our elected officials with some very seductive arguments for why they should not be made to go away.

At some point we should start hearing about how helpful these amazing surveillance technologies and techniques will be for helping local law enforcement and first responders to Save Lives Right Here at Home, delivered by a barrage of standard-issue Cute Kids in Peril ads.