TFD on 20th Century Social Media

And if he’s really hardcore, he’ll be all fountain pen up in that letter.

My Reenactment of the Keller-Tufekci Debate

@writer: My interview with @crustyoldeditor is now live: http://lin.ky

@hipsociologist: @crustyoldeditor claims Twitter is replacing quality conversation with a bunch of shouting! What bullshit! See this study: http://lin.ky !

@hipsociologist: using that one study, I’m now going to bury @crustyoldeditor’s qualitative argument under a barrage of quantitative data!

@hipsociologist: And I’m going to broadcast it to all 6,000 of my followers instead of writing him personally!

@hipsociologist: Now I’m going to extrapolate an unsubstantiated alternative hypothesis! Eat that, @crustyoldeditor!

@hivemind: oh @hipsociologist you so totally pwned @crustyoldeditor! Twitter FTW!

Wagging The Long Tail

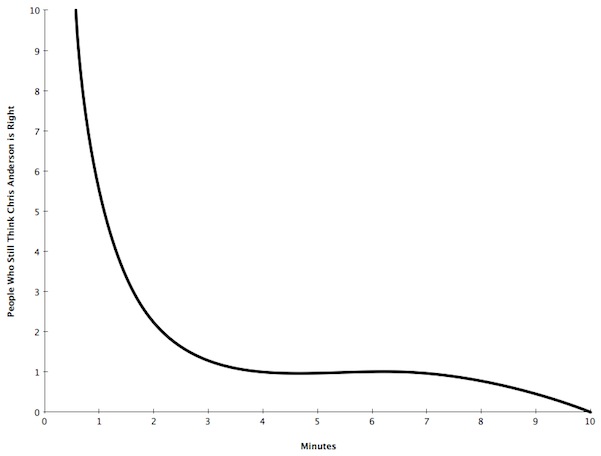

Can’t believe I came across a reference to Chris Anderson’s “long tail” this morning. Wow, I didn’t think anyone still remembered, considering:

What’s next, an article about the Cognitive Surplus? Ooh! Ooh! I know! The Singularity! (*eye roll*)

“People Like You Are Killing Bookstores”

Balticon 45 was a great experience. Gary and I had a lot of fun and met many new people whom we can count among our fannish friends and who have already had a measurable impact on Channel 37’s direction as well as its popularity in the community. But there was one sour note, and I’m taking a break from laying out a newsletter to get it off my chest.

Balticon 45 was a great experience. Gary and I had a lot of fun and met many new people whom we can count among our fannish friends and who have already had a measurable impact on Channel 37’s direction as well as its popularity in the community. But there was one sour note, and I’m taking a break from laying out a newsletter to get it off my chest.

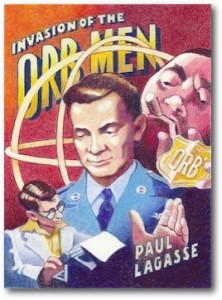

In addition to posting serial stories every week, Channel 37 sells e-books — “enhanced” versions of completed serials plus other books and stories that we have written outside of Channel 37. (And soon, some very cool audiobooks). So at our humble little vendor table at Balticon, we weren’t selling Channel 37 books, but rather giving away cards with QR codes to get to our site and learn more about us. It was also the official debut of Invasion of the Orb Men, my first SF novella.

So there we are early on the first day of the con, when this genial-looking older fellow comes over to the table and compliments me on the poster of the Orb Men cover that we had on display. We strike up a conversation and he asks about the book. I start telling him about it, and then he stops smiling and cuts me off abruptly. “You lost me at ‘e-book,'” he said. “I’m a bookseller. People like you are killing bookstores.” He continues on in that vein on for a minute or so before eventually walking away — not in a huff, but obviously not happy.

Throughout his complaint, I didn’t say anything — neither defending, placating, or apologizing. I just let him take his evidently heartfelt frustration out on me. Looking back on it, I think it’s because it didn’t really bother me that much. I felt then, and I feel now, that I have absolutely nothing to apologize for by selling my books in digital form. Online book buying flat-out blows the doors off of bookstores — and I love bookstores. I used to work in them, and I’ll still patronize indies until they’re gone. But they don’t have the monopoly on access anymore, and I seriously don’t have a problem with that. And I buy most of my books online now — from the publishers, direct from authors, through distributors like Amazon and Smashwords, through indie collectives like ABEBooks, and however anyone else wants to make them available to me.

It’s not going to be easy for the next 5-10 years for anyone in publishing, whether traditional or digital. There will end up being a Titanic-load of losers and a few winners shivering in the lifeboats. And that sucks for everyone involved, no doubt about it.

(On the other hand, when the big houses close, the streets of NYC will suddenly be awash in twenty-two year old editorial assistants panhandling for bubble gum, offering to sort Dumpsters into slush piles, and carrying “Will Be a Tastemaker for Food” signs. I’d buy a ticket to see that.)

So yeah, maybe I’m one of the guys who’s killing your bookstore, though judging from our sales numbers so far you’d be hard-pressed to prove it. I don’t know. But I think you’d be better off putting a lot of the blame on the publishers for sticking with models of publishing, distribution, rights, and royalty payment originally developed in the early 20th century while the Web was busy showing everyone who cared to look that there were vastly more efficient ways of handling those things. Blame the telcom and cable companies for making Internet access available to everyone and their dog for pennies. Blame customers for preferring to shop from the convenience of their own home instead of having to get in their car and drive to your store.

On second thought, I don’t think I’ve done that much to kill bookstores. Sorry.

On Optimism and Optimists

Last night I stumbled on the photos of the space shuttle Endeavour docked to the ISS that are floating around the interwebz. They stirred a strange jumble of feelings for me, and I ended up writing an essay about my reaction over on Channel 37 in an effort to sort it out. Take a look and see what you think.

Nine Years, Six Months, Twenty-Three Days

Now at last can we bring them home?

When Worlds Collide

Teching Towards Bethlehem — a Working Draft

This is a palimpsest of an essay for Channel 37. I need to work the kinks out here before posting it in the forthcoming “37 Minutes” category, where C37 authors can write things that aren’t serial chapters or news items. Hope it works…

So first, a bit of a preamble. Because I only recently came out of the closet and publicly embraced my fan-ness, I’m still catching up on all the brilliant writing about the SF field that appeared during my time in the wilderness. So it was only this morning that I learned about Charles Stross’s essay “Why I Hate Star Trek.” Well, I consider myself an old-school Trekkie, and yet (or perhaps, “because of that”) I find myself in general agreement with his argument that, particularly in Next Generation stories, the tendency of the writers to bolt SF elements on to stories as an afterthought like a spoiler on a Ford Escort negates the importance of science and technology in what’s supposed to be an SF story. The science and the technology should catalyze plot and character development, otherwise what’s the point?

On the other hand, unlike Stross I am not bothered by the fact that, for the most part, the characters all reset to zero at the end of each episode. That’s one of the potential limitations of weekly SF stories told through a box. More particularly, as told through a commercial box, in which advertisers want programs that bring the same — and more — eyeballs back every week. Numbers go down, show goes off the air. Publishing is not too different; that’s why everyone has to write series now. A core function of Strauss’ own Merchant Prince and Laundry Files series is to ensure that his growing reader base returns every time a new book comes out. Not an accusation or criticism, just pointing out the similar function. Sure, books let you evolve the characters more, instead of having to reset them every time like on TV. But that’s just because the box works differently than the book in trying to reach the same end.

So an observation followed by a question. The observation: SF stories are told in many media, and each medium has not only its tropes but its parameters of what works and what doesn’t. Writers have to somehow account for the tropes of the genre and the tropes of the medium together. The good writers are the ones who manage to pull that off.

The question: So what would an SF TV show look like that has:

- recurring characters

- an established universe

- respect for the standards of quality SF

- attractiveness to sponsors and advertisers

… and that doesn’t fall victim to either the “tech the tech to the tech” trap of ST:TNG or go off to the other extreme and degenerate into crowdsourced fanfic like the Battlestar Galactica remake (which Strauss says he also hates, but without having seen it)?

That’s what I want to think about for the next round here.

[Notes: Of course, the other tried-and-true way to build a TV audience aside from character reset is the soap opera. That’s the formula that BSG and many other SF shows since have tried to emulate. But we’re seeing indications that the soap opera approach, for whatever reason, doesn’t translate into a steady and growing audience base for SF as it does for, say, One Life to Live. Instead, it results in an ever-shrinking base of only the most diehard fans, while everyone else gets left behind — or jumps off — for one reason or another. Is it a generational thing? Is there something inherent in SF that doesn’t lend itself to the TV soap format? Are the viewing habits of SF fans really that different?]

The Word is Not God

This morning over a leisurely coffee I was reading a piece about Boris Pasternak and Dr. Zhivago (“He, the Living,” by Michael Weiss, in the New Criterion) when I read this:

Uncharacteristically for a poet of the twentieth century, Pasternak saw the depravity of Communism where it manifested itself earliest — in the Russian language. Yuri repeatedly registers his disillusionment with the epoch of “phrases and pathos,” the apparatchik’s cliche.

What struck me about this passage was how Pasternak saw that shifts in the usage of language often act as a barometer of where a culture is headed if things don’t change. With all the dramatic upheavals going on in the Middle East, the predominant language emerging from the tweets and Facebook posts is one of earthy practicality: food, jobs, equality, opportunity, fairness, justice. Here in the US, it feels as if our language is being hijacked as a tool of political terror, abstracted from any kind of rootedness in a common shared destiny. We are spending more and more energy outing people as ideological opponents, labeling people with some dreaded word that serves as a shorthand for otherness. “Liberal” and “conservative” don’t indicate a person’s political perspective anymore; they label the entire person, mark him or her as safe to keep or to expel from our gated village. And on TV and the radio and through the many channels of social media, this kind of branding has become a spectator sport, one that encourages the spectators to get in on the game and play too. We have in effect created a virtual national Coliseum, open 24/7 with an endless parade of undesirables being hauled up on stage to be fed to the slaughter for our blood-lust. And the people running the show for us are happy to have our attention focused there, and not on them. You want fries with your panem et circenses?

But this time it’s different, I hear. This time it’s really important, the stakes are so much higher. The unspoken and unacknowledged undertone: the reason last time wasn’t so important is because it wasn’t us.

The Great Experiment is at perpetual risk of being run off the rails by men and women whose short-sighted greed and opportunism are allowed to go unchecked. And as always, people of good will are outraged. But this time their outrage has yet to find a reality-based focus, as it has in the Middle East. Instead, we hurl blame at the convenient bogeymen who are served up to us, the perpetually unpersonified other who thinks, looks, or loves differently than we do. With the flick of a pen or the stroke of a key we can condemn whole groups of people at once, consign them verbally to a fate that we would then need feel no remorse should it actually befall them. And that is our great failing right here, right now: how can one feel compassion or empathy for, or kinship with, an abstraction? How can we see in the face of an alien a mirror of our own?

Language is the tool we use to represent a thing; it is not and can never be the thing itself. Language is also the most fundamentally powerful tool we have ever developed, the tool that has so far made all other tools possible. And since any tool can be a weapon depending on how you hold it, language is also our most dangerous weapon. In these precarious times, each of us needs to rediscover — and demonstrate — how to hold it properly again.